By Shanna Collins | July 27, 2016

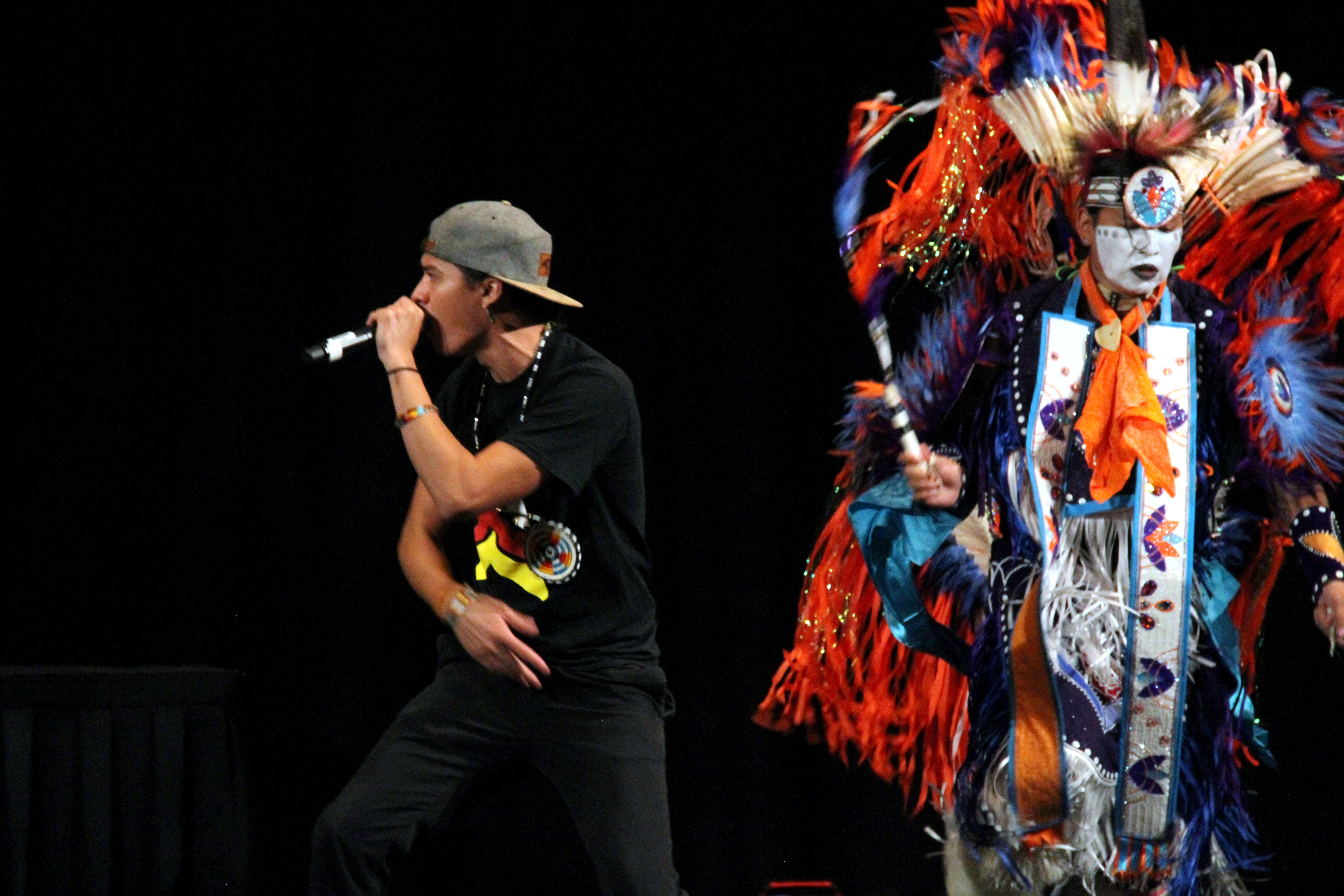

Frank Waln didn’t initially set out to be a rapper.

The Sicangu Lakota was born on the Rosebud Sioux Reservation in South Dakota, and was told to be something “practical.” He was the first person from his high school to get a full ride to Creighton University in Nebraska to study pre-med. After working at Indian Health Service hospital, he left Nebraska in order to pursue his dream of—you guessed it—music elsewhere.

It was when he moved to Chicago to study the audio arts and acoustics at Columbia College that his life found a new direction. “The culture shock I encountered when I moved to Chicago, realizing that people don’t know about Natives. The first week I was here, I met a girl who thought Native Americans were extinct,” Waln told In These Times in 2015. It was that conversation that would draw him to speak about his life as a Native American, about how historical trauma and cultural genocide are deeply embedded within that experience, and about healing his community.

Native Americans in the United States are still feeling the egregious effects of colonization: One in 10 deaths among Native Americans is alcohol related, with a high rate of alcohol fetal syndrome. The suicide rate on reservations is extremely high, with 40 percent of those taking their own life being between 15 and 24. One in four Native people live in poverty, with a high unemployment rate.

“As Indigenous people, we’re born into historical trauma and systems that were built on the destruction of our people,” Waln said. “I didn’t know I was poor growing up. We had our culture, family and beautiful things, even though there are drugs, alcohol and violence as a result of the history our ancestors faced. Growing up on the rez made me who I am. I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

His upcoming album, Tokiya, a Lakota word meaning, “first born”, “first creation” and “first of its kind” is both his first solo album and concept project. “A lot of it is telling the story of how I’m trying to deal and heal from the historical trauma that has been dealt to me through my ancestors and through being a survivor of genocide.”

The title of the album is also extremely important, as it sheds light on cultural loss of language that Native people experienced. “My great-great parents were the last people to learn [their] language because of the boarding schools and all that was done to try and wipe out our culture—so I’m trying to incorporate it in my creative process as much as I can.”

Waln seeks to discuss colonization of Native people in the United States while still respecting the hip-hop culture’s black origins, citing Nas, Dead Prez and Talib Kweli as influences on his rhythmic style. “As an artist, the challenges are complex and on multiple levels. My generation identified with hip-hop, but there were no opportunities to express that, let alone make music. Another obstacle that I’m still working through as an indigenous hip-hop artist is respecting the origins of hip-hop in black culture, and not erasing that.”

He also remains vigilant in drawing parallels between two marginalized communities. “Black folks are coming up out of a history of slavery that their ancestors had to endure. And my ancestors and myself we’re coming up out of a history of genocide—so we are both being oppressed by this system that was imposed on us,” he said in Here & Now earlier this year. “When I moved to Chicago, I started doing workshops and going to schools that were in inner-city Chicago. And I saw the parallels there and I didn’t even know they really existed. And then it started to make sense why I gravitated to that music and those stories.”