By Braudie Blais-Billie | January 13, 2016

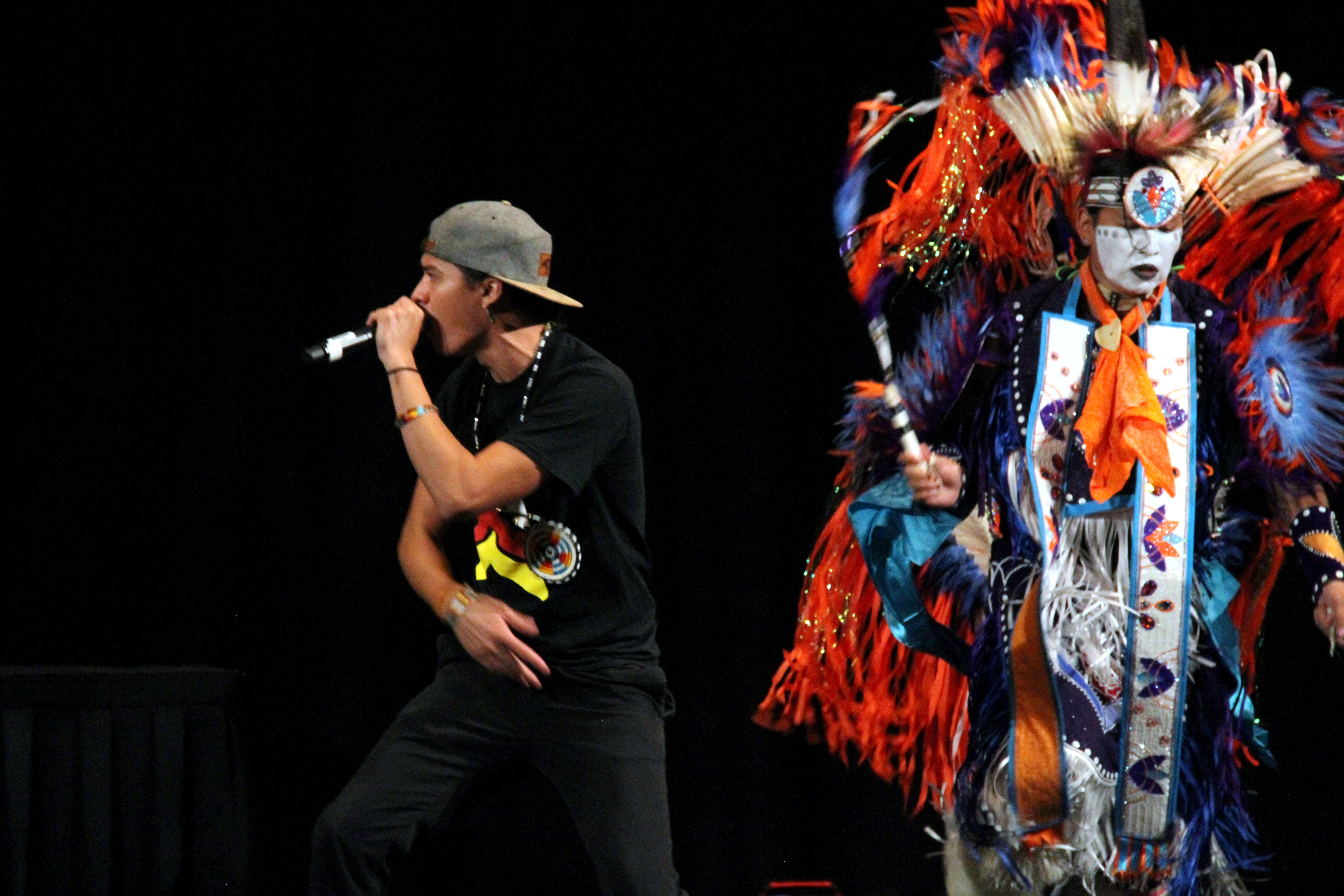

In today’s music industry, 26-year-old hip-hop artist Frank Waln is often described as a “Native American rapper” or “activist” — a figure who seems to effortlessly draw people in with his long braids, colorful production, and award-winning storytelling of his heritage and struggles.

Above all though, Waln is a Sicangu Lakota man tirelessly pursuing his passions and giving back to his loved ones. Growing up on the Rosebud Sioux reservation, Waln spent years teaching himself how to write, rap, produce, and perform and has fostered a unique sound and underlying confidence as a result. Crafting beats filled with fat drums, dynamic sampling, and a fresh perspective, Waln has become a leader for millennial indigenous (and non-indigenous) fans around the world.

And so whether you’ve been following his fight against the Keystone XL Pipeline or you’re tuning in as a new fan, Frank Waln is on the come up. Read our Q&A with the rising star below.

2015 has been a huge year for you: coverage in outlets like ESPN and Playboy, the success of MTV Rebel Music: Native America, and playing shows internationally. What’s it been like for you?

It’s been the best year of my life so far. The timing was crazy; I just graduated college, not knowing what my life would bring, and then all these amazing opportunities fell into my lap and it’s been snowballing all year. I was just in France this past October performing for this organization called CSIA. This has been the year I learned the most in my life.

You’ve talked about “symbolic annihilation” and negative Native representation in popular media before. Do you experience difficulties in your own representation since you’ve become more visible in mainstream media?

Yeah, almost weekly. The Playboy interview was the first time in my life I feel like I was treated like a dynamic artist. People approach me as if I’m an “activist” or just an “Indian.” Sometimes I don’t get the privilege to be treated like an artist.

As I’m becoming more visible outside of Indian Country, I’m learning not to fall into these paths of “this is what a Native should do” or “this is what a Native can talk about.” My manager and I really discuss every opportunity that comes our way, we’re really careful about how I’m portrayed for that reason. There’s also this pressure to speak for all Indians. You have to let the world know “this is my perspective, but I do not speak for all Indians.” It’s extra work and it’s tiring at times, but its just part of the path.

What can we expect from your upcoming debut album Tokiya?

This is my first ever solo album. I really love concept albums, so that’s the album I’m making. Tokiya is a Lakota word that means “first born,” “first creation,” or “first of it’s kind.” I’m currently re-learning my language. My great-great parents were the last people to learn the language because of the boarding schools and all that was done to try and wipe out our culture — so I’m trying to incorporate it in my creative process as much as I can.

I’ve had people from all walks of life tell me my music helps them be proud of their own indigeneity — whether they’re a black Indian growing up in an urban environment, or they have indigenous roots in South America. I keep that in mind as I make this album.

Reconnecting to indigeneity is kind of a working definition of decolonization, which is really hard to explain to people who don’t know the history of colonization in America. How would you explain decolonization?

I’m from the Rez [reservation] in South Dakota man, born and raised — then I went to school and learned how to speak about it in an academic language. The album is an example of how I’m trying to decolonize the way we talk about decolonization.

[ Tokiya] is my personal story of how I’m trying to heal from this historical trauma and the results of colonization. The colonizers needed to cut us off from the things that made us strong: our connection to the land, water, each other, our ceremonies, and our ancestors. I grew up disconnected from all that, and that’s why I’ve had a tormented childhood. I was lost, I didn’t know who I was, my dad abandoned me. But it’s all because of this complicated history.This album is me going through that and recognizing where those disconnections, traumas, and old pains come from, and how they manifest in issues we face as Native peoples today. Then, trying to heal from that and reconnect to the things that made Lakota people strong. As I’m actively reconnecting to my own culture and language, I’m bringing those concepts out in my songs and telling my story of how I’m using this music and my home community to heal.

As an artist, you gravitate towards hip-hop. Why is that?

On the reservation, those hip-hop artists were telling our story. Every time I saw a Native on TV it was so removed from our reality, but when I started listening to Nas and Talib Kweli they were telling stories that I identified with. One major element of hip-hop is that you can bring to it who you are. For me, it was a catalyst to reconnect to my own culture and own indigeneity and look at it from a non-colonial lens. It was a safe space to look at who I was as a Lakota person.

In an interview with In These Times you talked about your concern of respecting the origins of hip-hop in black culture. How are you adapting hip-hop to your Lakota culture?

I’m creating hip-hop songs from a Lakota perspective and looking at the way my ancestors framed our songs, whether that be a pow wow or ceremony song. They’re short, powerful phrases repeated. Something I love about Lakota music that’s very important to me is the drums; you just hear it and know you’re home. As a producer, I’m going in on the drums. I want them to hit you in the heart. A good example is my new track “Victory Song.”

A lot of this album is about place and space. I want people to feel what it’s like to be where I’m from. I want them to know what it smells like, tastes like, what the wind feels like, what historical trauma and hope feels like. I want to try and musically take people there.

Top three albums you’re listening to right now?

Future’s DS2 has been on repeat since it came out. His cadences are crazy, man. I have Burial’s Untrue on vinyl so I’ve been listening to that a lot. Fleetwood Mac’s Rumors is always in rotation — I grew up with my mom playing that album, so it’s ingrained in my soul.

What’s something you want people to know about you that they don’t already know?

I’m actually a really shy, introverted person. Like very low-key emo. When I first started making music, I kept it a secret for two years! I only like attention on stage, so when people treat me like I’m famous it weirds me out.

Any plans for the near future?

I’m trying to get my album out sometime this winter and play as many shows as I can. As a young indigenous artist from a reservation with these opportunities and platforms, I feel a responsibility to bring more opportunity home. My manager, Tanaya Winder, also manages Tall Paul and Mic Jordan. The four of us started a scholarship called the Dream Warriors Scholarship for Native American high schoolers that want to be artists. Last year was our first year, and I’m excited to build off of that.