By Dawn Turner Trice | April 22, 2014

Frank Waln and his mother used to go for long walks on their South Dakota reservation. One evening about a decade ago, when Waln was 12, he saw an object in a ditch that caught the last bit of sunlight.

It was a CD, and although it was terribly scratched, Waln took it home and played it. The disc skipped a few times, but soon rapper Eminem was telling his story of growing up white and poor in Detroit.

On the Rosebud Indian Reservation where country music dominated the radio, this was Waln’s introduction to rap music.

“I knew hip-hop resonated with the youth on my rez, but I never had a personal experience with it until that moment,” said Waln, 24, a Lakota rapper who’s about to graduate from Columbia College. “It changed my life.”

That’s because it reflected his life — the struggles, but also the will to overcome. Waln said it’s that resilience that’s too often omitted from accounts of the Native American experience. He refers to one-dimensional depictions as “poverty porn” and feels strongly about Native Americans telling their own story.

Rap — not the gangsta, misogynistic stuff — is the perfect art form because it dovetails nicely with native people’s oral tradition of storytelling.

“From the time we come out of the womb, we have this heaviness in our spirits and hearts and mind,” Waln said. “I was introverted and depressed, and music gave me a way to work through all of that.”

From his song, “Oil 4 Blood,” Waln raps:

Tell Diane Sawyer I am a warrior/ Give me your camera, send Peltier your lawyer/ Free all my people get them out of prison/ Take them to Sundance show them how we’re livin’

Rap began in the mid-1970s as a way for black, Hispanic and Afro-Caribbean youths in New York City housing projects to rail against fatherlessness, unemployment, drugs and police brutality. Waln said the music connects with young Native Americans today who are dealing with similar issues.

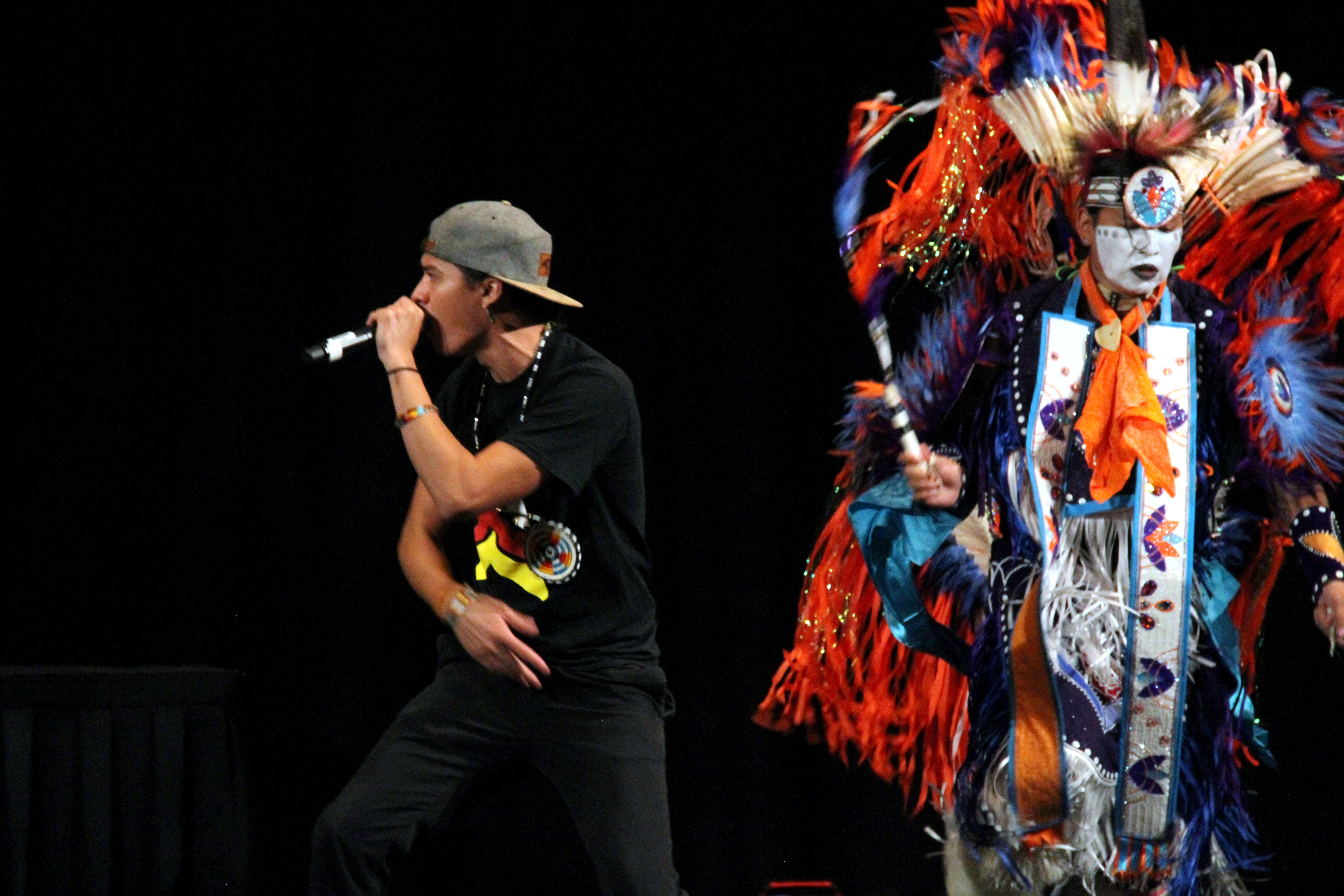

His music combines the drumbeats and flute sounds that are the backbone of Native American music with the spoken word that is the heartbeat of rap. His lyrics are about growing up without a father; about borders that are made by governments and those that are self-inflicted; about education, oppression and even the Keystone XL pipeline.

One of Waln’s recurring themes deals with the Native American fight against invisibility. He said many Americans know very little about indigenous people because they’re either misrepresented or underrepresented. He said the result is “symbolic annihilation.”

“There are people who aren’t even aware that we exist in real life,” he said. “They go to (natural history) museums and see exhibits about Native Americans and think we’re a people of the past. But we’re a people with a past, not of the past.”

In “Hear My Cry,” Waln sings about the way Native American images are exploited and misappropriated:

I was born red, stained with the blood of genocide/ Now all mascots the only way that I’m identified/ Blackhawk, Red Skin, the image of our dead men/ Dressed in the headdress, my people it’s depressing

Waln recently asked his classmates to guess how many federally recognized tribes there are in this country.

“They said five to 20,” he said. “The answer is 566. None of this is even taught in schools, and it does us all a disservice.”

Waln said the Rosebud reservation, where his family still lives, is in one of the poorest counties in the nation. Few people leave the reservation to pursue higher education. But Waln’s path was different.

Valedictorian of his senior class, he said he was the first student at his high school to earn a Gates Millennium scholarship. It took him to Creighton University in Omaha, Neb., where he majored in pre-med.

“Everybody around me was saying be a doctor or a lawyer, so you can come back and help the community,” said Waln, a Rogers Park resident. “It took me two years to figure out that I could follow my dream of making music.”

He came to Chicago to attend Columbia College and when he arrived, he found the noise, the crowds and the fast pace disorienting. And, although he’d spent time in Omaha, he’d never seen so many skyscrapers or so much concrete and steel.

“Everything was so disconnected from nature,” Waln said. “Back on the rez, it’s the plains and everything is wide open. I also realized for the first time in my life that I was poor and not everyone had to struggle, and it helped me see the bigger picture and start to question things and think critically about my reality.”

Next month, Waln will graduate with a bachelor’s degree in audio design and production. But he will stay in the city for a while to continue his work with Native American students in Chicago Public Schools.

With his music, he’s traveled the country and has won Native American Music Awards. On Tuesday he’s performing at Marquette University for Earth Day, and later this week he’ll be in Washington, D.C., to perform at a Keystone pipeline protest.

He said he’s committed to returning to his reservation and describes himself as an activist who uses music and other art forms to improve the community.

I asked Waln if older relatives and neighbors back home worry that native traditions might get lost in rap.

“They see the poisonous aspects of hip-hop that are cherry-picked by the (studios) and amplified,” he said. “But when elders see me perform, they seem to like what I do. They see that there are different elements to hip-hop and it can be empowering and holistic.”